The emergency-use authorizations of COVID-19 vaccines are priming consumers for vaccine brand differentiation and presenting a novel marketing situation that tasks marketers with challenging master brand decisions.

Inevitably, the first question asked of someone who just received the COVID-19 vaccine is, “Which one did you get? Pfizer? Moderna? J&J?”

Consumers are not just aware of the COVID-19 vaccine parent company brands, but many have specific preferences. When was the last time consumers seemed to care about the manufacturer associated with a vaccine? In the past, for consumers, it was typically just “the flu shot.” A few highly informed consumers may have been aware of different characteristics of a flu vaccine such as “quadrivalent” or “65+” but, in general, there was no significant awareness of a specific brand or manufacturer. And with the possible exception of a few vaccine brands such as Prevnar, the same is true for most other vaccines, with consumers typically unaware of what brand they are receiving. Even for healthcare professionals, there was often little distinction and, therefore, little to no brand preference (aside from cost).

Pfizer has branded its COVID-19 vaccine Comirnaty, but it remains to be seen how quickly the brand name will be widely adopted. Regardless, the Pfizer connection is still prominent today and it is difficult to imagine a future world in which we refer to all our COVID-19 inoculations generically as “the COVID vaccine.” There are several reasons this category dynamic has developed in this way:

- In an emergency use authorization (EUA) scenario, with no commercialization and no formal product brand launch, health officials and the media all needed a consumer-friendly way to reference these vaccines even while still in development. In addition, since the two leading vaccines use the same mRNA technology, they needed to be differentiated. For the media, the manufacturers became a natural identifier, as the primary focus was on “who,” while the “how” became secondary. If development timelines had been different, perhaps we would be talking about the “mRNA vaccine” vs. the “adenovirus vaccine.” Instead, however, we have the “Pfizer vaccine” vs. the “Moderna vaccine.”

- From the beginning, the media has conditioned consumers to think of these vaccines as different, pinning one manufacturer versus the other in a race to authorization. This narrative also established demand – a feat pharma and HCPs typically work very hard to achieve with many other vaccines. The premise that there is a need for a COVID-19 vaccine was already clear (vaccine skeptics notwithstanding).

- As mainstream media has incessantly reported on each of the manufacturers’ vaccine’s efficacy and safety data, storage differences, number of shots required, and supply issues—never before have consumers been so acutely aware of who is making their vaccines and how they differ. It is important to note that given EUA, these messages aren’t coming from the pharma companies themselves, but rather from an objective source.

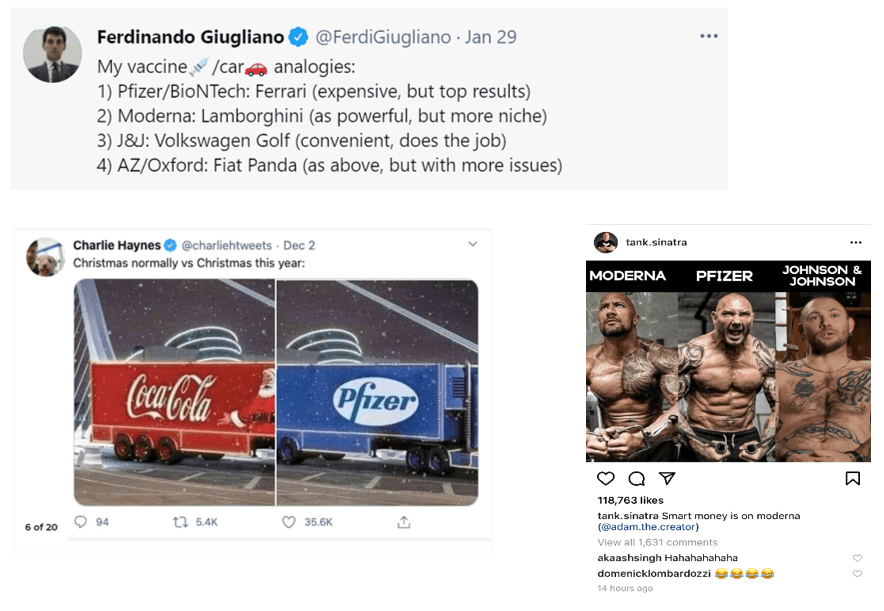

For what must be the first time in history, pop culture and Big Pharma have collided, with tweets circulating memes of the competing pharma companies and even car analogies. Consumers are engaging with Big Pharma in new ways and on every social media platform. As a result, there is unprecedented vaccine manufacturer differentiation among the general public, and where there is differentiation there are de facto brands. It just took the mainstream media to get consumers to care.

“Consumers are engaging with Big Pharma in new ways and on every social media platform.”

Perceptions are being shaped now, not only around the vaccine products, but also around the parent company brands which are now inextricably linked with the COVID-19 vaccines. Notably, however, a voice is missing in shaping these perceptions: the pharma companies themselves. Never in recent history has a consumers’ awareness (and experience) of a pharmaceutical product come before commercialization, while also being completely tied to the parent company name. This unprecedented situation creates challenges, but also presents rare opportunity for pharma companies. For so long, these parent companies have been distant entities, usually not directly associated with specific products. Now, consumers are paying attention.

So now what?

COVID-19 vaccine companies must make unique product and parent company branding decisions. They will be confronted with not only building a brand, but also evolving corporate brand associations that they had little part in shaping during EUA. What will that evolution look like? Consumers have been getting their information from the media and have seen PSAs for COVID-19 vaccines from government agencies like the CDC and state and local health agencies. How will the messages change, and how will consumers respond when they come directly from the pharma companies?

The major COVID-19 vaccine manufacturers will also need to consider eventually shifting their vaccine from a corporate brand to a product brand, but that still doesn’t address how they should manage their master/corporate brand following the transition. Pfizer’s vaccine (the Ferrari) was the first to be authorized in the US, has a 95% efficacy message and fewer reported side effects than Moderna’s vaccine.[1] Thus, perceptions of Pfizer, the master brand, are currently extremely favorable. How will Pfizer take the momentum of the goodwill (and great product) established during EUA into commercialization? The company recently changed its corporate logo for the first time in 70 years, moving from the familiar pill-shaped logo to a design that evokes a DNA double helix. Is this more than a nod to its scientific direction? Perhaps a signal that it is anticipating greater prominence of its master brand in the future? A logo to remind everyone that they are cure creators? And if Pfizer’s corporate brand has the potential to benefit from a halo effect, then AstraZeneca and J&J have the opposite problem. Traditionally, a key rationale for pharmaceutical companies not pursuing master brand strategies has been that an issue with one product could taint all products carrying the master brand label. With a challenging roll-out, negative press, and safety concerns would consumers start doubting other AstraZeneca and J&J products if they tried to attach their corporate brands?

“The major COVID-19 vaccine manufacturers will also need to consider eventually shifting their vaccine from a corporate brand to a product brand.”

Underlying all of these brand decisions should be a consideration of consumers’ desire to continue to receive information and know who they are receiving that information from. A byproduct of the global attention on these vaccines has been a new level of transparency. For instance, consumers know the number of doses to be delivered each week from a given manufacturer or a vaccine’s efficacy against new variants. To what extent will this level of transparency continue without the benefit of the media doing the heavy lifting? Now that there is a precedent in touting data with consumers, will we see other vaccine brands educating consumers on immunogenicity and including an efficacy angle? It can be a slippery slope, and consumers deserve to be armed with the tools to properly differentiate vaccines if that is what the messaging is telling them to do.

Transparent messaging is one thing, but the source is another. In a recent HawkPartners survey, we asked nearly 10,000 respondents in which industries they felt it was most important for a brand to showcase its authenticity. Pharma was the top industry chosen, by two-thirds of respondents. Our latest Brand Authenticity Index shows that now that pharma is so squarely in the public eye and so central to ending the global health crisis, consumers are demanding to more deeply understand who the pharma companies are and what their values are.

Traditionally, trust is a key pillar of brand loyalty, and trust is also a cornerstone of authenticity. In healthcare, with patients and healthcare professionals alike, we consistently hear a proven track record or longevity is a tenet of trust. Have Moderna and BioNTech turned this staple principle on its head? Will manufacturer supply delays or unkept production promises (which normally consumers would never know about) impact consumers’ perception of trust?

“…now that pharma is so squarely in the public eye and so central to ending the global health crisis, consumers are demanding to more deeply understand who the pharma companies are and what their values are.”

We are in unconventional times, and it is unclear how far traditional thinking will take us. While the full impact of the EUA vaccine roll-out remains to be seen, a few things look certain. Going forward, consumers will think about their vaccines differently, and the manufacturer brands will likely remain in the spotlight. Perhaps consumers won’t stop with vaccines and will start looking for the master brand for other therapeutics as well. The pharma industry has the opportunity to take advantage of this newfound awareness, and not just awareness but receptivity. Pharma, the longtime villain, is now the health hero and has the ear of US consumers. It is no longer what is pharma pushing, but how is pharma helping? The seed of trust is there but will require transparency and authenticity. Are pharma companies ready to establish a trust relationship with consumers?

[1]Chapin-Bardales, J., Gee, J., & Myers, T. (2021, April 5). Reactogenicity Following Receipt of mRNA-Based COVID-19 Vaccines. JAMA. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2778441.